One year after the UK vote to leave the EU, cracks are beginning to show in the economy. This Atradius report offers an update on the current situation and insolvency outlook.

Summary

- The UK economy has been remarkably resilient since the vote to leave the EU, but one year on, growth is being increasingly challenged. Inflation is the main culprit as real wage growth has turned negative, squeezing household purchasing power.

- UK insolvencies have been rising since Q3 of 2016 and are forecast to increase 6% this year and 8% next year. Business failures are expected to be concentrated in consumer-facing sectors like retail and accommodation and those that depend on imported materials like construction.

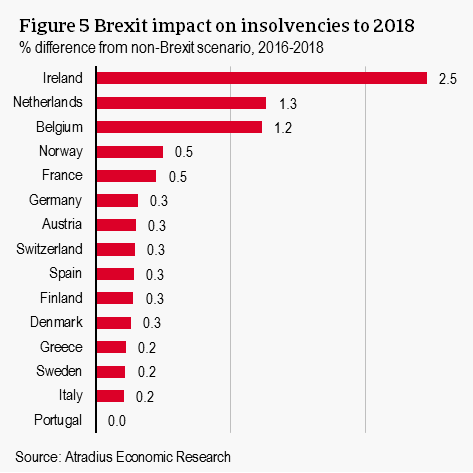

- Effects on the rest of Europe have been limited so far, especially as domestic politics have thus far bucked the trend towards populism, easing uncertainty. But we still forecast insolvencies in 2017-2018 to be higher in Europe than if there was no Brexit, particularly in those countries with close economic ties to the UK like Ireland, the Netherlands and Belgium.

UK economy: resilient and stable, but

inflation beginning to bite

In the aftermath of the 23 June 2016 decision to leave the EU, the UK economy has been surprisingly resilient. After an initial shock, confidence quickly rebounded and consumers continued to support solid economic growth. A sharp depreciation of the pound sterling also contributed to higher growth, boosting manufacturing exports in particular. But now the flipside of the weak pound sterling is beginning to ease momentum as it weighs on consumer spending.

The pound sterling has depreciated about 14% relative to the euro and USD compared to June 2016, with most of the adjustment taking place directly after the referendum. This increases the costs of imported goods, which, coupled with the recovery in oil prices since early 2016, is driving up prices. Annual consumer price inflation has reached 2.7% in April 2017, the highest level since August 2013. Despite the lowest unemployment rate in over 40 years (4.6%) and robust employment growth, wages have not kept up with inflation, in part due to relatively low productivity growth. In March 2017, wages grew only 2.1% y-o-y, suggesting a contraction in real wages, or decreasing consumer spending power.

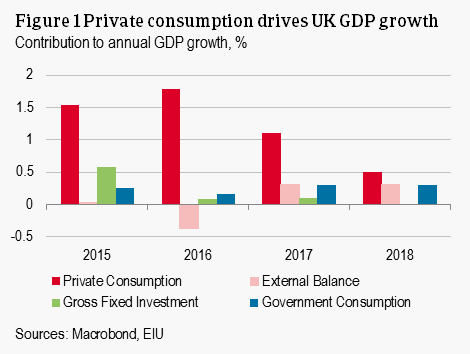

Private consumption drove 1.8% GDP growth out of a total 1.8% growth experienced in 2016 (net exports cancelled out the small contributions of government consumption and fixed investment). GDP growth slowed to 0.2% q-o-q in Q1 of 2017, down from an average quarterly rate of 0.6% in 2016 and marked the slowest pace in four years. As expected, the slowdown is concentrated in consumer-focused industries like retail and hospitality (though this should be partially offset by higher foreign visitors to the UK, attracted by the weaker pound sterling (+4% in 2016). This comes at a time of low household savings rates – only 3.3% in Q4 of 2016. Furthermore, in 2017 consumer credit conditions are expected to tighten for the first time in six years.

With low savings, tightening access to credit, and slipping real wages, private consumption is forecast to slow in 2017 but remain positive. It is expected to fuel 1.1% growth in GDP in 2017. Higher government consumption and a positive contribution from the external balance, thanks to more competitive exports, will help to keep annual GDP growth stable around 1.7%. Business investment has held up better than expected, but still slowed to 0.5% y-o-y in 2016, from 3.4% in 2015. It is expected to be stable in 2017, in part due to the long-term nature of most investment. However, as negotiations with the EU heat up, we expect uncertainty to play an increasingly negative role, halving private consumption’s contribution to GDP and bringing growth from investment to a standstill in 2018.

Corporate insolvencies to increase in the UK

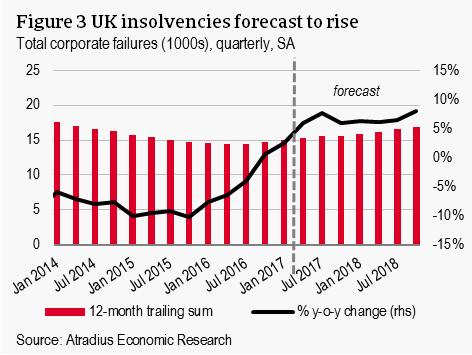

Insolvencies rose by 1% in the UK in 2016 for the first year since 2011. In Q1 of 2017, the UK Insolvency Service estimates that 3,967 companies entered insolvency, a 4.5% q-o-q increase and 5.3% y-o-y increase. This marks the third consecutive quarterly increase in business failures.

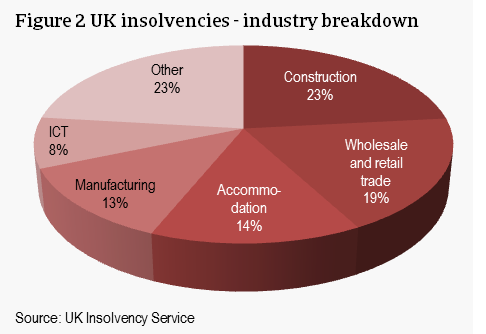

An industry-level breakdown shows that last year’s insolvencies were concentrated in the Construction, Retail, and Hospitality sectors. The construction sector generally has the highest insolvencies per year in the UK, due to the high number of small firms and intense competition. With pound depreciation, these firms are particularly exposed to higher costs for imported raw materials which have been squeezing profit margins and are expected to be more pronounced in 2017. The retail and accommodation sectors are also expected to see elevated insolvencies in 2017 and 2018 due to weaker consumption. These sectors will also see their balance sheets challenged in 2017 with the implementation of the National Living Wage (the obligatory minimum wage) and the rollout of pension auto-enrolment to smaller firms.

Furthermore, the foreign-exchange hedges that protected many firms from pound volatility in the aftermath of the referendum are also beginning to expire, which could exacerbate the pain for importers.

Some sectors are seeing improving insolvency performance though. The weak pound helped boost Agriculture sector income in 2016 supporting an 8% decline in sector insolvencies. Manufacturing also benefitted from the weak pound as it boosts the foreign competitiveness of UK manufactured goods. Insolvencies in that sector fell 5% in 2016. UK exports are further supported by more robust growth in the eurozone.

The UK insolvency outlook for 2017 and 2018, however, remains negative. Consumer-oriented sectors account for a much larger share of the total economy – services account for about 80% of GDP with industry covering only 20%. We expect that the current trends will continue and even increase through the remainder of the year. 2018 should be even more difficult as business investment dries up. The total number of nationwide insolvencies is forecast to increase 6% in 2017 and 8% in 2018.

Impact on EU is limited thus far but short-term outlook is not immune to spill-overs

Immediate economic fall-out for the EU in the aftermath of the UK’s membership referendum was largely limited. It was expected that uncertainty would adversely affect economic growth in EU countries with close trade and investment ties to the UK already. Confidence, however, is holding up and stock markets continue to reach new highs. Furthermore, in the period prior to the snap election in June, uncertainty had eased as the Brexit situation had proven more stable than predicted. However, the unexpected election result heralds a further period of uncertainty.

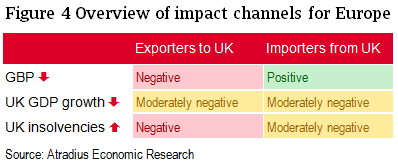

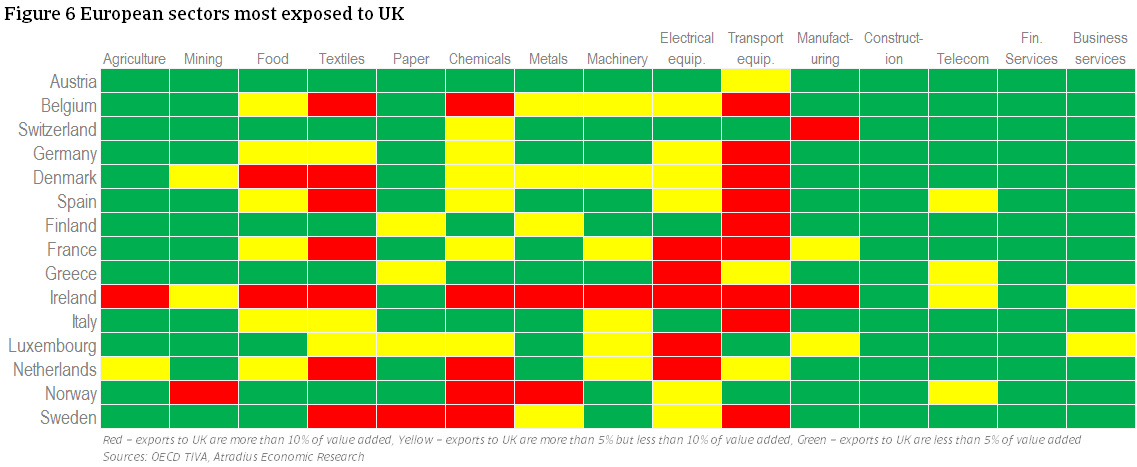

We expect negative effects to increase in the rest of the year and 2018 as negotiations intensify, especially if it remains uncertainty whether a deal can be struck. However, the magnitude of the negative impact is lower than predicted last June. An overview of the direct, short-term impacts is presented in the heat table below. A weaker GBP means a stronger euro for firms trading with the UK – this benefits importers and hurts exporters. Any country or firm that is involved with the UK also could suffer from lower GDP growth and higher insolvencies in the UK.

In terms of economic and financial linkages to the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Belgium are the most vulnerable. These countries are followed by France, Germany and Spain. On top of the identified direct impact channels, increasing uncertainty should weigh on both UK and EU confidence and financial conditions, weighing on activity in EU countries through both channels. The OECD estimates that this could have a negative impact of about 1% lower GDP across the EU compared to a baseline scenario with no Brexit from 2016-2018. Since insolvencies are closely aligned with the business cycle, changes in GDP growth developments have an effect on insolvency growth developments. We predict a similar magnitude increase in business failures largely corresponding to the countries most exposed to the UK. The projected impact on insolvencies until 2018 is presented below – presenting the difference in the total number of insolvencies from 2016 to 2018 compared to the no-Brexit scenario.

Ireland is clearly the most vulnerable, with strong economic, geographic and historical ties. We forecast that corporate failures will be 2.5% higher there. Ireland is followed by the Netherlands and Belgium with 1.3% and 1.2% higher insolvencies respectively. The remainder of surveyed Europe is only expected to see very mild impacts.

Looking to the sectoral level, a heat map of major industries by European country is presented in Figure 6. This is determined simply by the export exposure to the UK. Overall, the UK imports a significant share of value added in the Chemicals, Transport, and Textiles industries from Europe. More domestically-based, non-export intensive industries like Construction and Financial Services are well-insulated from spill-overs. At the country level, Ireland faces the most broad-based negative consequences from a weaker British pound and slower growth there, as nearly all sectors are flagged red. The Benelux and Nordic countries also face moderate impacts on a wide range of exporting sectors.

Outlook

The UK economy is forecast to see steady but slowing GDP growth in the coming two years. Increasing inflation, stemming primarily from the weak pound, is the main driver of slower GDP growth and higher insolvencies thus far. This is expected to translate into higher insolvencies in the UK: up 6% this year and 8% next year. Economic growth across European countries also remains steady, though lacklustre, with a more limited impact of Brexit than previously predicted. The insolvency outlook across the rest of the continent is still relatively positive, but we still estimate that insolvencies may be mildly higher across nearly all countries than would have been the case if the UK were to remain in the EU.

Documents associés

663KB PDF