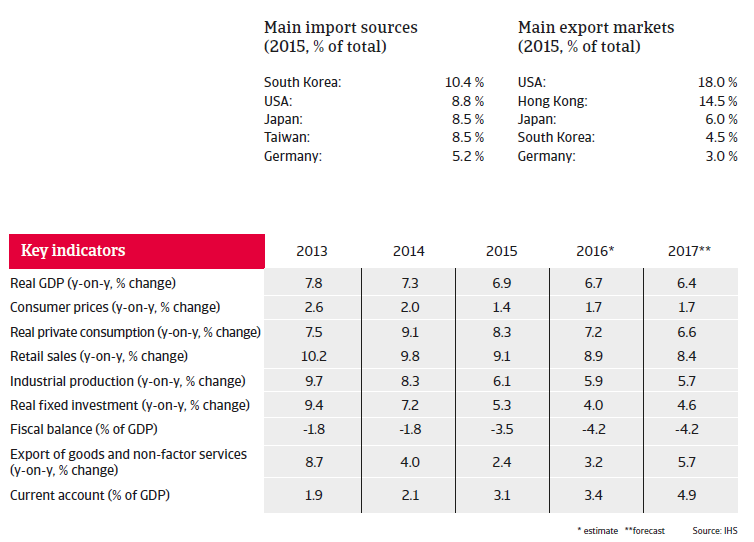

The on-going economic slowdown, overcapacities and high indebtedness of many businesses will lead to further increasing business insolvencies in 2017.

Industries performance

Insolvencies expected to increase further in 2017

The current economic slowdown has led to increasing overdue invoices and businesses requesting longer payment terms – a trend that is expected to continue in 2017.

Insolvencies are also expected to rise further after a substantial increase in 2016, as overcapacity and high indebtedness remain an issue in many sectors (especially construction, steel and metals, shipping, mining, paper). While listed and state-owned businesses still benefit from stronger support from banks and shareholders, more caution is recommended when dealing with small and medium-sized private businesses, as many of them - even those active in better-performing industries - often suffer from limited financing facilities.

Political situation

Head of state: President and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping (since March 2013)

Head of government: Prime Minister Li Keqiang (since March 2013)

Form of government: One-party system, ruled by the CCP

Population: 1.38 billion

President Xi is firmly in power

Overall, the domestic political situation in China is stable, with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) firmly in power. President Xi Jinping continues to consolidate his power within the CCP and is seen as the most powerful Chinese leader since Deng Xiaoping. The government under Xi has launched a campaign against corruption and extravagance by top party officials, leading to the conviction of several prominent party members. To prevent any major social unrest, the administration’s main aim is to preserve economic growth, create jobs and develop a public welfare safety net. So far, protests have flared up only locally and have been swiftly contained by the security forces.

Internationally Sino-US relations have been generally stable, but it cannot be ruled out that tensions increase due to potential shifts in the US China policy under the new Trump administration. Regionally, China´s grown assertiveness in the South China Sea conflict and the conflict over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands with Japan will remain issues.

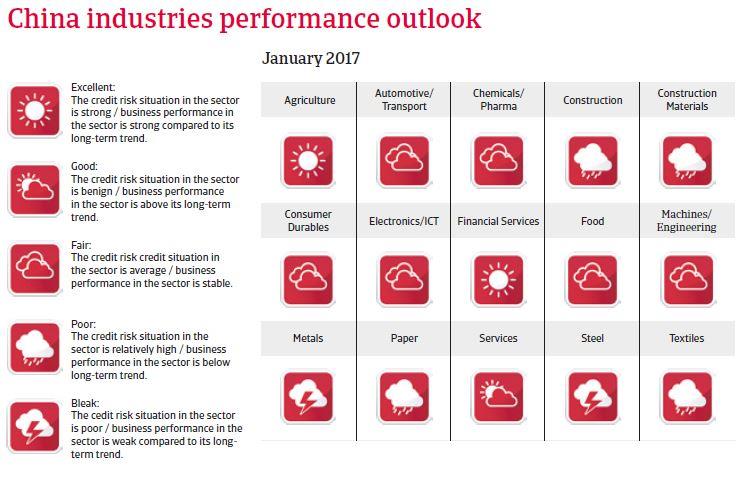

Economic situation

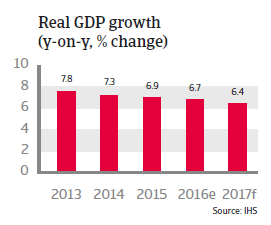

Growth expected to slow down further in 2017

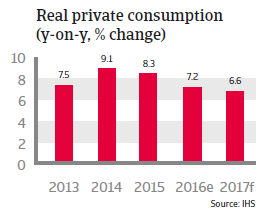

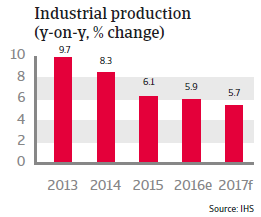

China’s economic slowdown continued in 2016, although at a slower pace than estimated at the beginning of last year, dampening international worries of a hard landing. In 2017 GDP growth is expected to slow down again, to about 6.4%, with private consumption and industrial production growth cooling down further.

Chinese authorities have repeatedly stressed the willingness to use monetary and fiscal means to maintain the targeted growth levels of 6%-6.5%. Chinese policy communication has improved and the probability of a disorderly depreciation of the renminbi has become lower. Thus a hard landing is increasingly unrealistic, at least in 2017, but the risk has not completely disappeared.

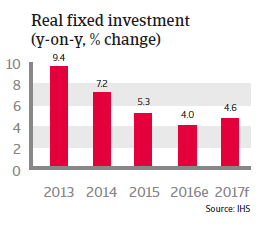

The main reason for the slowing annual growth since 2013 is not so much the dedicated economic rebalancing – away from export-oriented investments to more consumption-led growth – but decreasing productivity growth, with labour productivity decreasing sharply since 2010. The progress towards rebalancing has been limited so far: consumption as a share of GDP has increased slightly, but is still very low (at about 38% of GDP), while investment remains the primary driver of growth.

The perils of high debt

While a sharp economic slowdown has been avoided, it is worrying that investment-driven GDP growth is helped by strong credit expansion, of which much is used for developments in the real estate sector and infrastructure projects. In 2008, debt (government, business and individual combined) was about 150% of GDP, and it grew to more than 250% of GDP in 2016. Because credit expansion is much higher than the economy’s growth rate, capital cannot be used in an efficient way for investment or consumption, and the sharp debt increase has raised fears of a potential financial crisis. The financial vulnerabilities visible in the financial, corporate, and real estate sectors and in the local government are interconnected - a shock in one sector could lead to a chain reaction and impact others.

That said, Chinese authorities are aware of those risks and have taken some actions, e.g. measures to restrain house prices. Most troubled are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which account for just 20% of industrial output, but absorb about half of all bank lending. There is a need to restructure highly indebted companies, especially in industries with overcapacity, like aluminum, cement, coal, construction, and steel. While the authorities have started to address the issue by moderating credit growth and starting to restructure the sectors worst off, a more comprehensive and centrally-led approach is needed.

The tools the authorities have at hand will most likely allow China to avoid a debt crisis and a hard landing. The central government has tight control over the economic and financial activity in the country. As the bulk of the credits is public debt and lenders are often state-owned, banks can be instructed to refinance debt.

Public and external debt are very low and China has huge international reserves, so there is room for both monetary and fiscal stimulus if needed. There are capital controls in place to limit the risk of capital flight. This all creates a cushion for the economy in the event of any external or internal shocks.

Decline of productivity affects long-term growth prospects

China’s total factor productivity, which is a measure of an economy´s long-term dynamism, has continuously weakened in recent years, and it seems this trend will continue until annual GDP growth stabilises at a level of about 4%.

The key to raising productivity growth and to create room for deleveraging would be to implement more economic and social reforms, in order to proceed from low-grade industrial production to a modern center of innovation. However, for the time being it seems rather improbable that the Chinese government will give market forces a large-enough role to stimulate innovation. The number of large and unprofitable SOEs remains too high and their role too dominant in certain sectors (e.g. oil, mining, telecom, utilities and transport). Another stumbling block for productivity growth is financial restrictions imposed by the government, which lead to misallocations of capital. Still, too much investment goes to the real estate sector and SOEs, and too little to the services sector.